I was set to do this piece as columnist duty (I’m a columnist now!!) but the press pass fell through. I decided the night before that I would buy a ticket on resale and go to the show anyway because it was too good to pass up as an intellectual exercise. Here is everything I would have written in the published piece, but with a certain extra blog-specific je ne sais quois.

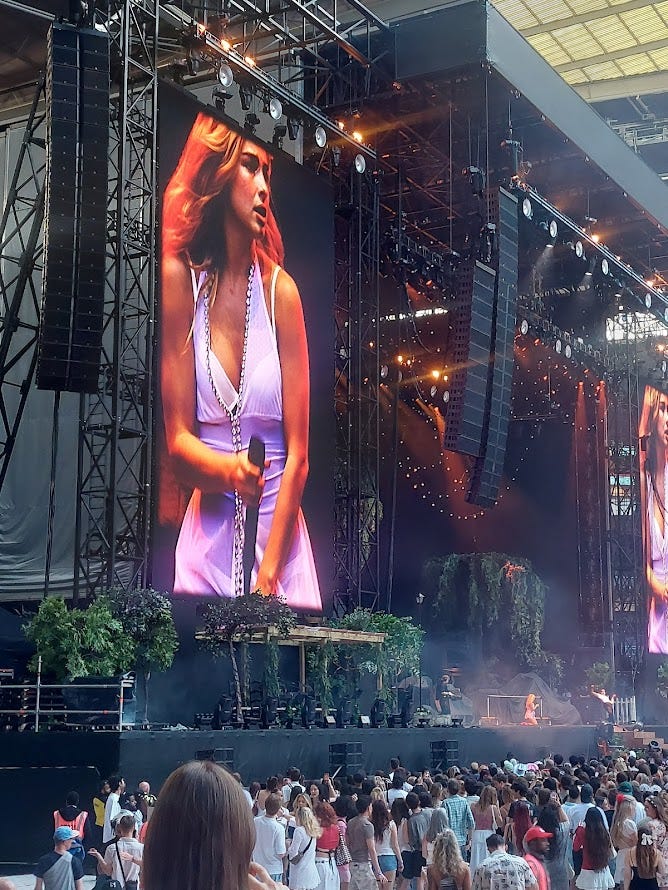

The event: Lana Del Rey playing Wembley Stadium. Addison Rae as support act; gospel choir, live strings and electric guitar, ballerinas, pyrotechnics, etc.

The star rating: Probably millions, but difficult to count because they are not in a row. They have scattered everywhere and are colliding constantly like individual particles of gas. :・゚✧*:・゚✧・゚:⋆ ˚。⋆୨୧˚✧༝┉.⋆。⋆☂˚。⋆。˚☽˚。⋆.˚*❋ ❋*˚┉༝✧

1.

The big pop stars are sort of like saints, and we find out about the lives of saints from symbolically rich images. In our manic multimedia age it is both comforting and fun to think that each pop star has a ‘clue’: some single event or photograph or quotation or piece of work that will make sense later as an explanatory key to their entire career. For Michael Jackson this was probably the burns injury he sustained on the set of a Pepsi ad, exactly halfway through his life; for Madonna it is most likely the bit in the Truth or Dare documentary where she tries and fails to seduce Antonio Banderas. Lana Del Rey’s clue is the first bit of Eliot’s Four Quartets, which appears as an interlude on the Honeymoon album:

Lana is a Spenglerian pop star. She gets earthier and more interesting as time goes on, but her actual body of work runs through history like a codebreaking cypher. Its reference points are not letters of the alphabet but five decades of the 20th century; 30s-40s-50s-60s-70s. Sometimes two or three align at the same time; sometimes the spinning mechanism malfunctions and we snap back and forth between two contradictory things,. When we’re done with imaginary Woodstock we loop around to the equally-imaginary agricultural fantasy of Kazan’s Baby Doll, Laughton’s Night of the Hunter, and Fleming’s Wizard of Oz. (Sepia tornado footage plays at the start of her UK and Ireland Tour. We have been sucked in.)

No matter what happens, we are never allowed to break the cycle and enter into the 1980s. It is too brash and plastic and not distant enough; for some of Lana’s early online fans it is actually in living memory. Its new pop sound and new blockbuster structure create a continuity with our own cultural moment; it feels too much like birth and innovation and not enough like death and decline. Lana is almost always mentioned in conjunction with Old Hollywood but the past few years have seen her slouching further towards New Hollywood, the domain of Elia Kazan, Montgomery Clift, Tennessee Williams, the jazz soundtrack, Robert Altman, the Actors’ Studio (thus also late-stage Marilyn), and the Coppolas.

This is significant because it is the last Hollywood period in which the star system remains an active and exploitable ingredient. Robert Aldrich manages to make dark, Gothic puppet shows out of the Crawford-Davis feud; Elizabeth Taylor is plucked from the MGM schoolhouse and starts playing distraught Southern belles. Garbo’s disappearance is significant enough in the public imagination to sustain two separate alternate histories. Polanski’s Chinatown is ostensibly about the California water wars but also very clearly really about the film industry. We get more than our fair share of nostalgia for the musical and the mystery film, but our dancers and detectives usually end up wandering around aimlessly, as if searching for something that does not actually exist.

This works for Lana because she is all about distance. She’s about as far from the past she sings about as she is from the immediate present. A large volume of her songs take place in the furthest reaches of memory; she almost always sings in the first person, so the listener can either insert herself or become her armchair psychologist. Before the pandemic-era induction of her real-life sister, mother, father and grandfather, the only recognisable figures in her songs were mercurial celebrities, the ones who generally died young and had already been papered over with lots of mythology - Marilyn, Elvis, James Dean, Jim Morrison.1 Paradoxically, this deliberate distancing from history brings her closer than any other modern celebrity to the highest castes of Classic Hollywood. Quentin Crisp explains this well:

The remoteness makes it difficult to set up a legacy in the conventional way. The crowd at Wembley did not entirely go mad for Addison Rae’s opening set, but they did go mad for Diet Pepsi - and they went stratospherically mad later when she repeated it on stage with Lana. It is a very good song, the perfect emulation of the best ones on Born to Die. For the women who have attempted to live perpetually in Lana’s universe it provides some hope that it can be extended into other corners of the world, and perhaps even peopled with other characters.

We deceive ourselves about the possibilities here, and so does Addison. She has clearly read at least one Madonna biography. She knows that if you want to establish yourself in a certain arena it is wise to cling onto a fixed constellation of historical personages - they are best-placed to pass on the Mandate of Heaven. Madonna has used Martha Graham, Marlene Dietrich, and Marilyn Monroe; Addison has used Madonna, Britney, Lana, and Judy Garland. We get the sense here that she’s treading very recent ground; Sabrina Carpenter only went on the up after opening for Taylor Swift on parts of the Eras Tour. Now she’s her proverbial ‘daughter.’ Audiences are primed to accept a one-to-one ratio of pop queen to pop princess.

Lana might give Addison Rae a popularity boost, but she will never truly be a pop progenitor. This is because she has no progenitors herself. Her closest human references are all fictional characters, members of the pre-Tumblr collective imagination. Most have existed over several decades and in several different media. She has been most of the women in most filmed Tennessee Williams plays, but she is most strikingly Liz Taylor as Catherine Holly in Suddenly Last Summer (see the brilliant video for Ultraviolence) and Carroll Baker as Baby Doll in Baby Doll (see Lana’s brilliant prairie house set on this tour, with occasional projections of her upper body into the first-floor window - Flowers In the Attic style). Her current red sky projections mean she is also Scarlett O’Hara - she of the book-and-film-and-TV-show-and-unofficial-sequel, standing firm on the wrong side of a war it is perhaps unwise to bring up.

In certain older songs she is Lolita from Lolita, but this controversial tendency gets unmanageable at 40 (Williams has roles for all ages). You can see why Lolita was an early subject. In the original novel she’s camouflaged by the intellectual deceit of the narrator, and her visual identification is shared out equally between the two actresses, 30 years apart, who tried to make a movie out of her. Faces and voices recede - all that matters now are the long American highways, the sprinklers in suburban gardens, and the vague sensory experience of getting kidnapped by a much older man.

Here Marshall McLuhan’s ‘hot’ and ‘cool’ distinction makes a lot of sense - Madonna is the ‘hot’ radio news show, stuffed with unidirectional information, and Lana is the ‘cool’ phone call, dependent on conversation and bound to its invisible context. Lana suggests an imaginary world and leaves most of it empty, so listeners can participate; Madonna succeeds by worming her way into threads of existing narrative, leaving no space for anyone else. She manages her quotations, callbacks and coincidences with the might and zeal of an MGM executive from the 1930s. She casts herself as Eva Peron by suggesting the dictator’s wife is her own historical parallel; the casting story becomes part of the mythology. Critics call her a postmodernist but she’s too Type A for postmodernism; she accidentally invents history all over again.

Fans still remember Lana’s Nabokov thing perfectly well; at Wembley thousands of them were wearing heart-shaped sunglasses. The general effect was uncomfortable, and it confirmed my suspicions: Lana’s project turns sour when it sidles too close to the real world. You are meant to grasp it in decontextualised snatches of archival footage, not in terms of actual lives with beginnings and endings. If Lou Reed had actually lived to feature on Brooklyn Baby he would have ruined the distance, and thus the entire point. Lana’s own personal life ostensibly does happen in the real world, but it only resonates because we hear about it in snatches. Her Fordham degree, her weight loss travails, her newfound romance with a proprietor of alligator tours - it all seems so much more melodramatic when we are trusted to fill in the gaps. This is because a) we have been listening to her music, b) we have all been on Tumblr.

2.

There is no question that Lana Del Rey is a Tumblr artist, probably the most Tumblr artist of all time. Tumblr was a political engine, but also a mass exercise in manufacturing a historical imagination. Hundreds of thousands of teenage girls sat in their rooms, collaging the past century together by consensus. In Lana’s early videos you can see the collaging at play. Video Games is a moving Tumblr dashboard, alternating between cartoons, digital paparazzi footage, grainy zooms into the Hollywood sign, and home movies from indiscernible bits of the twentieth century. The remarkable Mermaid Motel (ahead of its time in 2008ish) splices together Murnau’s Nosferatu and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

What you get from all this collaging in the end is a series of ‘aesthetics,’ continuous groupings of visuals and sounds you could imagine existing at the same time and in the same place. Some of them eventually flowed onto TikTok, where they became buyable fashion and interior trends - a ‘hot’ establishment to contrast with the more interactive ‘cool’ one. But the original incarnation remains, lurking under the surface of the new-look internet. I define this original incarnation more neatly as a place and time with no people in it.

The vernacular nature of the mass exercise removes anything that is not relatable to everyone; on the ‘aesthetic internet’ the common denominators are the photographs you can imagine yourself living in. Always big are the anonymous bedrooms, gardens, palm trees, sunsets, bits of the Tokyo subway; the shots taken by women looking down at their own legs; hands holding nice drinks; bits of identikit packaging from multinational designer brands; runway ‘details’ (ie. a single shoe or bag). All film screenshots on Tumblr eventually become ‘faceless’ - either on purpose or because the faces blur together and cancel each other out en masse, as with the two sister versions of Lolita.

Lana once contributed in a personal capacity to the ‘aesthetic internet,’ and her work feeds perfectly into its mass consciousness. It is almost all in the first person; it is immersive, with rushes of strings and walls of sound. It relies on tiny signifiers of place and time, collaged together in verse the way you might collage together a Tumblr dashboard. She is the only artist who could remain here, completely unscathed, for over ten years. She taught everyone how to compile from history at will, but her visuals and lyrics ended up seeping into the Tumblr mass-machine themselves; in ye olde days you couldn’t move an inch down your dashboard without bumping into a GIF from the National Anthem video or the spoken monologue from Ride, which played to great excitement on the UK and Ireland tour.

I have been convinced about my ‘Total Theory of Lana Del Rey’ since I was about 13. Her space for interpretation lends itself to this kind of intellectual bravado; I am convinced that every other woman at Wembley was also convinced of their own Total Theory of Lana Del Rey. An entire generation has passed - her new teenage fans are mostly on Pinterest and talk about a ‘2014 revival’ - but her music is more integral than ever to the churn of what is now called ‘online girlhood.’ The original few Lana eras are another repository to mine, Lana-style, for visually resonant diamonds. This is how she gets us - if we follow her lead, her own canon will get more precious as it shrinks from whatever cultural moment we are in. Her music is about nothing lasting forever - but she has outrun forever.

My top 10 Lana songs, not in order: For K Part 2; Shades of Cool; Sweet; Venice Bitch; Yayo; Raise Me Up (Mississippi South); Oh Say Can You See; Fingertips; Swan Song, A&W (I’ll probably change my mind about this like tomorrow)

‘Harvey’ on Cola is a pre-Me Too Harvey Weinstein - but Lana later admitted to inserting him as a vague ‘character’ in the vein of Citizen Kane. They were never personally involved. The lyric was later changed to ‘Ah, he’s.’

Ella, this is just fantastic cultural crit.

Very anabolic. I would describe this as a good workout. My breath has been taken away.